Like many foreigners who move to Japan, I work in the ESL industry. Currently, I teach students ranging from 6 months old to those in their 60s. But hell, this ain’t my first rodeo. I have a degree in education, and I’ve taught worldwide for the entirety of my adulthood. My students have run the gamut from bilingual toddlers to aspiring writers at universities, from public to private schoolers, from city-dwellers to country folk, from able-bodied to disabled, from native speakers to language learners. While teaching is a notoriously fraught career choice and the pay is at least as brutal as rumored, teaching also comes with its unique joys.

Chief among those, for me, is hearing the answers to a simple question I ask every one of my students at one point (or several points): “What’s your favorite (insert category here)?” For toddlers it may be animals or colors, for older kids it is hobbies and books and movies, and, when I sense another otaku in my midst? It’s anime, of course.

I’ve always gotten a broad range of answers, but some anime seem universally beloved. Evangelion fans are everywhere, and many of us are adamant Shinji apologists. When I taught elementary schoolers in Chula Vista, Dragon Ball Z and Naruto were king even in the 2010s, and kids who were way too young for tragic violence were obsessed with Tokyo Ghoul; a few years later, writing workshop attendees gushed to me about Mob Psycho (2016-2022)but also, inevitably, Death Note (2006).

Now that I live in Japan, I’ve gotten a few more unexpected answers. One high schooler told me her favorite manga is The Darwin Incident, a story about a human-chimpanzee hybrid, while another told me about how watching Mawaru Penguindrum changed how he thought about the world (I agree, but damn, that was an awesome conversation I never expected to have in 2023!). A parent I teach bonds with her daughter over their shared love for the eye-candy-ikemen period drama Touken Ranbu. They visit themed cafes and shrines housing famous swords featured in the show.

Here in Tottori, when I bring up one of my all-time favorite series, Fullmetal Alchemist (all iterations, okay), my students seem confused only until I say the Japanese name (Hagane no Renkinjutsushi), and then they let out exclamations of recognition. Even if they’ve never seen it, its reputation remains profound.

But what happens when I mention Cowboy Bebop, the cult-classic space Western that many American fans consider an undisputed anime GOAT?

Crickets. Well, no, not crickets… cicadas, because cicadas are still screaming here, and that’s how loud the lack of response is.

And it isn’t about the name. Cowboy Bebop, written in katakana, is カウボーイビバップ, or Kaubōi Bibappu. Even in the years immediately following Netflix’s disappointing live-action adaptation, Cowboy Bebop is mostly very absent from the modern Japanese zeitgeist. I am sure others have delved into why Cowboy Bebop looms so large in the hearts of Western fans despite being mostly forgotten in its motherland, but here goes…

A Little Backstory

At twenty-six years old, Bebop is downright retro these days. Millennial Americans were first introduced to Spike and Jet at midnight on September 2nd, 2001, when Cowboy Bebop became the first anime to air on Cartoon Network’s ambitious, then-new programming block, Adult Swim.

By that point, the series was already two years old. Directed by Shinichiro Watanabe and impeccably scored by Yoko Kanno, the neo-noir classic about bounty hunters in space debuted on TV Tokyo in June of 1998.

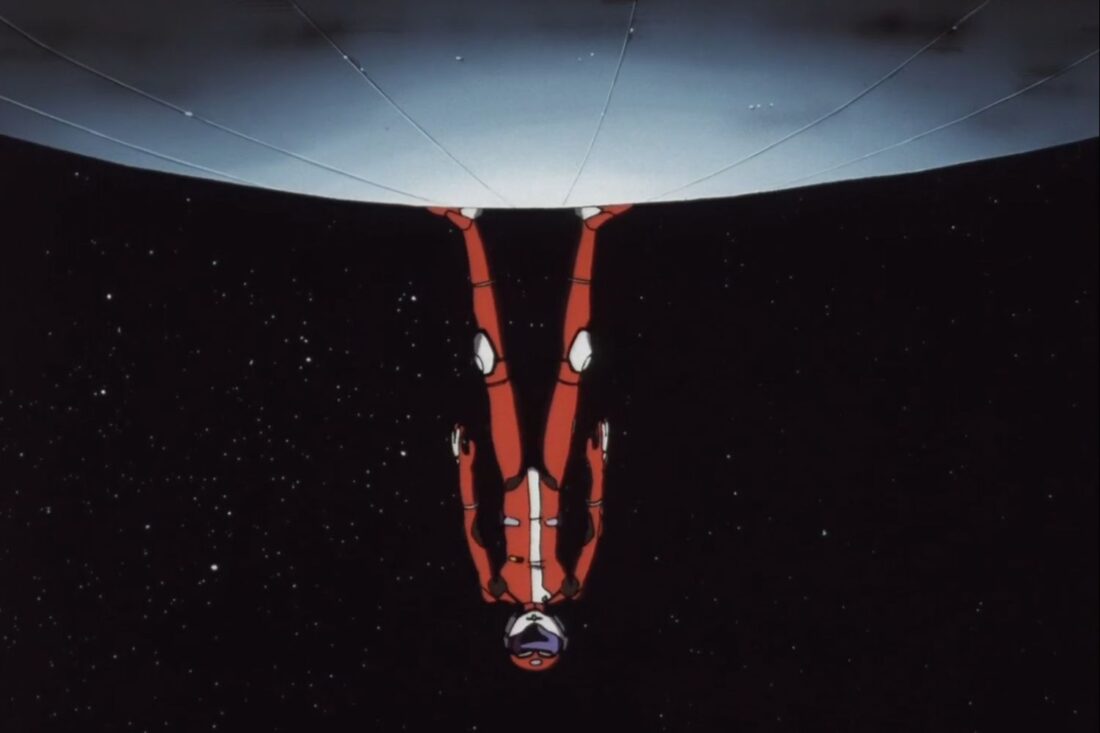

Wildly, when Bandai gave Watanabe the green light to create a space-themed anime, it was on the sole condition that whatever series he created feature spaceships that could be sold as toys. Talk about a wide range of possibilities, but somehow Watanabe managed to draft a neo-noir show aimed at jaded adults who were unlikely to buy many toys. Bandai’s toy department dropped the project like the hottest of potatoes, but thankfully, a different branch of Bandai lent its support instead. Watanabe finally had free rein to write and direct a show that meant more to him, and to others, than selling a few thousand model kits.

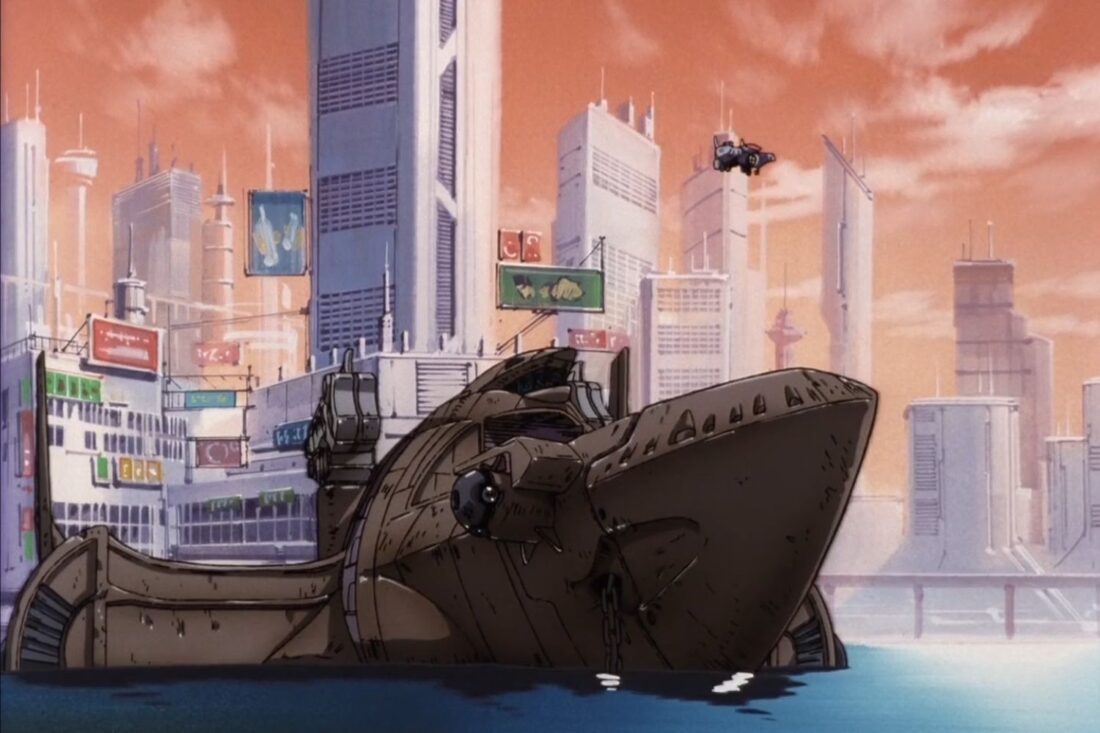

I don’t know if anyone needs an introduction, but here’s a summary of Bebop: a ragtag gang of bounty hunters traverses the galaxy in a beaten-up fishing ship, the eponymous Bebop. The show is mostly episodic, with most episodes featuring the crew’s encounters with different intergalactic criminals, be it a crime syndicate leader in the Tijuana asteroid colony, a hijacker transporting a plant that may cure his sister of Venus sickness, or prison inmates who’ve commandeered a prison ship.

Watanabe and legendary animation studio Sunrise approached each storyline as though it were a standalone film—and a classic film to boot. The show is rife with Western genre tropes like standoffs and saloons and train heists, as well as with neo-noir staples like grizzled old lawmen, dimly lit bars, and plenty of moral ambiguity. Settings range from space-station casinos to terraformed no-man’s lands, and the characters? Yeah, they don’t like discussing the past. Neon is on the menu, as are stylish fight scenes and roses in rain puddles.

Most episodes are impeccably written, and all are sublimely scored by renowned composer Yoko Kanno, previously acclaimed for her work on Ghost in the Shell. Kanno, performing as the leader of an outfit known as SEATBELTS, mixes jazz, orchestral music, blues, funk, pop, and rock with gorgeous abandon, creating an iconic soundtrack that remains unparalleled to this day.

There’s so much to admire here, but there’s very little praise I could heap on Bebop that hasn’t been heaped aplenty by countless others. I would argue, however, that Bebop is only elevated to classic status because the show sticks the landing, with its last few episodes delivering emotional punches that validate the entire series preceding them.

Neo-noir speculative fiction ages well because it is intentionally anachronistic, an old storyline deliberately displaced in time. There are many reasons to love Blade Runner, but maybe the setting is half of them. And though space Westerns are difficult to nail, Firefly, despite the stain Whedon has left on his projects and legacy, deserves much of its cult-classic status. Cowboy Bebop feels somehow like the transcendent marriage of these two difficult genres, and more to boot.

Cowboy Bebop has always been the embodiment of cool. It was then, and it is now, in part because its creators came at the project with both nostalgia and the future in mind. But what does it mean to be cool, and why does this particular brand of cool resonate more in the West?

The Toonami Effect

For decades now, anime has been gaining more traction outside of Japan. What once felt like a niche, irredeemably geeky hobby for most Americans—so much so that people like me were “anime-closeted” for years—is now widely embraced and even, well, popular. Given the easy accessibility of anime in an internet world, this makes sense, but I still feel a little delighted when I visit a random Hot Topic shop in the States and see it full of My Hero Academia and Studio Ghibli merch. Oh, what validating awe my younger self would have felt if, after driving two hours in the northern Michigan winter snow to the nearest shopping mall in Traverse City, I could have spent twenty bucks on a Spirited Away tee!

Anime was introduced to most people in my generation by way of Pokemon and Dragon Ball Z on the WB and Sailor Moon on UPN. But later, more profoundly, Cartoon Network’s Toonami became America’s main proliferator of Japanese animation. It remained so for almost a decade before online piracy made anime immediately accessible to the cunning youth. Starting in 1997, CGI hosts Moltar and later the robot mascot T.O.M., at the helm of his spaceship, presented audiences with everything from modern American classics like The Powerpuff Girls to Japanese imports like Robotech, Gundam Wing, The Big O, and Outlaw Star. Toonami’s success led to Cartoon Network launching Adult Swim in 2001, and the first anime that Adult Swim ever aired? Bebop.

For teens, staying up to watch Adult Swim was a social no-brainer. Adult Swim was effective at bridging the gap between childhood and adulthood. For all kinds of weird reasons, Disney and the country’s Puritan roots included, American culture really struggles with a notion that is very easily understood in Japan; animation is the medium, not the genre, and really can be tailored to all ages. Sure, shonen shows are aimed at kids and teens, but josei manga and anime are written for adult women.

Before Adult Swim, American teens had to either put aside “childish” things or get by watching The Simpsons. Adult Swim offered a desirable alternative for those who wanted to enjoy animation without the stigma of being immature. I’ve met many otaku over the years, at cons and clubs, who specifically cite Bebop as their gateway anime. The power a gateway series holds is hard to match.

But in Japan? Cowboy Bebop did not define a generation or open the minds of a population uncomfortable with the notion that animation could be for adults and be serious. Its initial impact in Japan was that of a show misplaced in a 6 PM timeslot because violent action sequences aren’t ideal for family dinners. Later, the series aired in full to critical appreciation. Cowboy Bebop, however quietly groundbreaking, was no one in Japan’s first anime.

Western Themes, Western Dreams

Watanabe was trying to create something unique with Bebop. Initially, the show claimed to belong to a “brand new genre.” But this was the Tarantino-tainted ’90s, a decade on the cusp of the millennium. Pulp fiction, cyberpunk, and Westerns were having a heyday, and Bebop was, despite its since-established timelessness, very much a product of its time.

Consider this: in the same year that Sunrise produced Bebop, Dark City and The Truman Show were released in the States. Men In Black had just left cinemas and Wild Wild West had begun production. Gattaca and The Fifth Element came out in 1997, and the world was only months away from being blown away by The Matrix. Grunge was dying, Y2k loomed, and science fiction cinema was a welcome consolation. If the future could not be avoided, at least it could be entertaining. Meanwhile, prominent anime film releases in 1997 included Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue and The End of Evangelion. In both countries, themes of existentialism and fear of technology were par for the course at the end of the century, but so were hopes that the future would not totally suck, and might even be kinda neat.

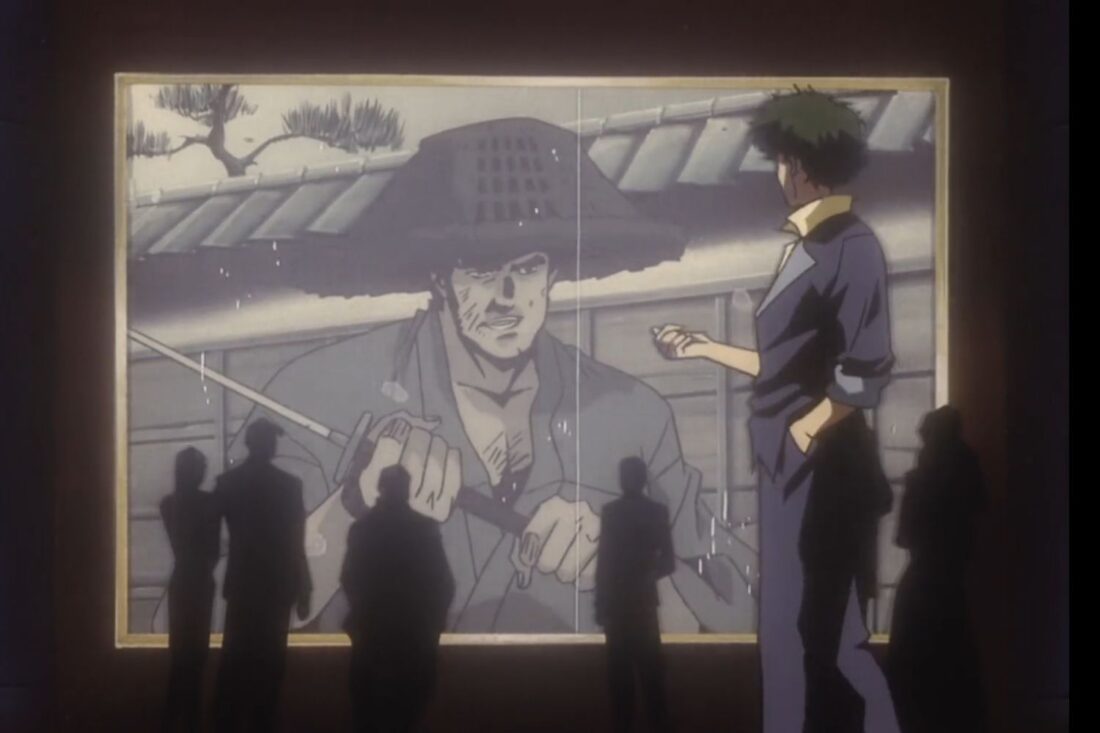

Watanabe took inspiration from international cinema. There are salutes to the samurai films of Kurosawa, and Spike’s design was very much modeled on Lupin III, an iconic Tezuka character. But Western staples are possibly even more omnipresent. Spike practices Jeet Kune Do, the martial art pioneered by Bruce Lee. Jet, the Bebop’s grizzled captain, records captain’s logs echoing classic Star Trek, and in an episode centered around hallucinogenic mushrooms, the crew comes face-to-face with a pair of characters that have fallen right out of a Blaxploitation film. There are references to Alien’s face-huggers, 2001: A Space Odyssey, spaghetti Westerns, and the Desperado franchise. Similarly, the series is informed by novels from the likes of Raymond Chandler and William Gibson.

What Was Your Gateway Anime?

While these more Western references seem to have perennial appeal in the US, many of them evoke less nostalgia for Japanese audiences. In the world of anime programming, trends change quickly and drastically; publishers and studios need to be ready for those shifts. By the time Bebop found its Western audience, the late ’90s were over and Japanese pop culture had taken a sharp turn down a darker path. While Hollywood slowly turned away from space in favor of superheroes and fantasy epics, Japan was cornering a unique market with modern horror classics like Ringu, Audition, and Battle Royale. Just as quickly as the fascination with space Westerns and cyberpunk Americana had arrived, it had left, replaced by gone, replaced by a provocative subgenre that was more distinctly Japanese.

And so, in Japan, Bebop remains very much a ’90s thing, part of a trend as temporary and cyclical as, say, zombie fiction or isekai. It may come back around, but it doesn’t hang around.

The Otaku Dilemma

Anime has long since been a natural part of the entertainment landscape in Japan. Most people I talk to here discuss their favorite dramas and anime interchangeably, because aside from being animated, anime and variety shows and dramas are all just…television. Of course, for anime devotees, it’s different.

Whereas “otaku” has been adopted as a proud self-identifier by many Western anime fans, otakuis a word that makes Japanese people distinctly uncomfortable. In Japan, to be an otaku is to obsess over something—anything—to the point of detriment. Here, otaku need not be anime-obsessed; there are densha otaku who travel the country to take photos of unique trains, and wota, idol otaku who sleep with life-sized body pillows of real idols, and gunji-ota who basically do accurate military cosplay for fun. The otaku label does not exclusively pertain to anime fans; any hobbyist can be labeled an otaku if ever their hobby threatens to overtake their life.

In America, living for one’s passions is often romanticized. In Japan, to embrace the otaku lifestyle is to embrace a specific form of social isolation. In the States, outsiders are encouraged to find and support each other and the rest of the world can fuck off if they don’t like it. In Japan, similar communities form, but are sometimes tainted by a misplaced sense of shame.

I would argue that stories about conquering unknown frontiers will always hold an especially poignant place in the hearts of Westerners, as problematic though this notion may be. Cowboy Bebop remains that special, rare gift: a show that can be recommended to almost anyone. For science fiction fans teetering on the edge of anime fandom, who may be put off by fanservice or the art or some other overwhelming negative that seem ubiquitous from an outside perspective, Cowboy Bebop feels remarkably safe. It lacks gore, it lacks any egregious fanservice (Faye’s yellow outfit being an exception), and its mature themes of loneliness and living aimlessly resonate deeply for many people.

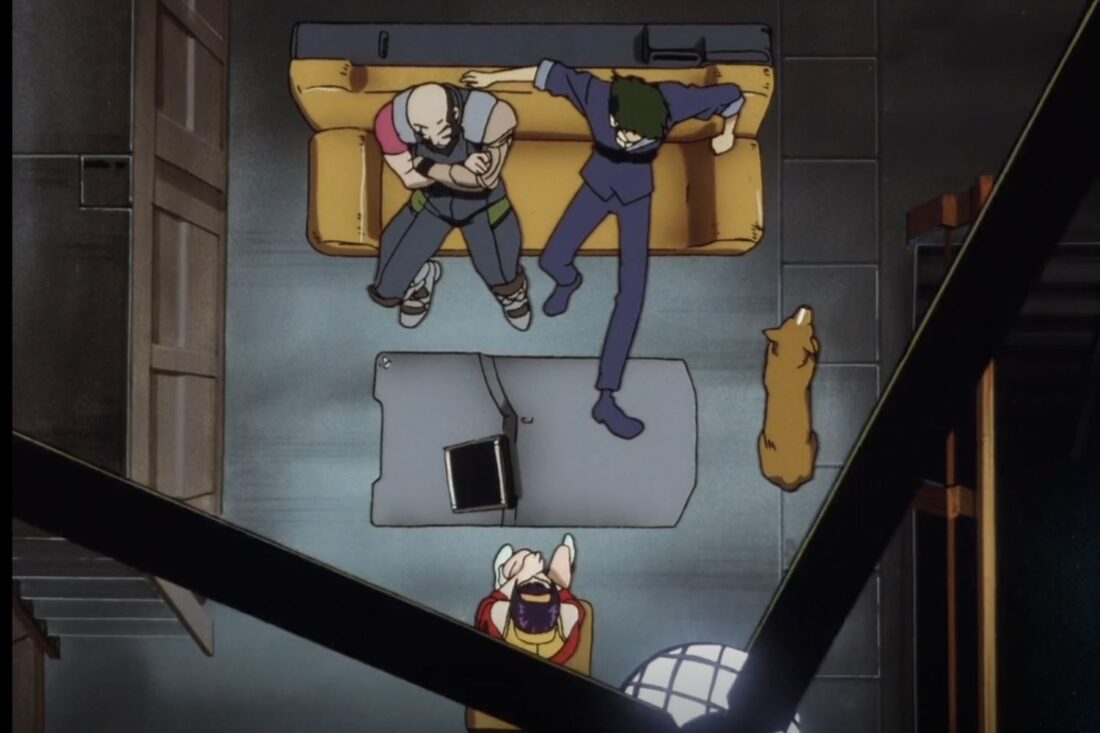

But Bebop is not about people who conquer anything. Instead, it’s a found family story about a group of would-be wastrels, a former criminal and a woman displaced in time and a disillusioned cop and an orphan who, briefly, find solace in each other aboard an old ship. The central heart of the series, unspoken but painfully omnipresent even during comedic moments, is this: the Bebop crew aren’t just traveling through space for fun or bounties; they are all running away from something, either the past or themselves, and ultimately, they will fail to escape.

Whatever else it may be, Cowboy Bebop is a story about doomed misfits. Americans pine for that quintessential us-against-the-world struggle, and celebrate it even when it ends in flames. And the nuance here is important, as are the cultural connotations surrounding the show. Because the misfit gang element is not what sets Bebop apart—many of the most internationally successful anime feature oddball gangs of outsiders who learn to function as a whole.

That’s the key difference, here. Aboard the Bebop, the camaraderie is never quite enough to keep the ship afloat. When the characters make sacrifices, they do so to rectify the past rather than to build a better future. Inevitably, they fail to succeed as a group, despite their affection for each other. This is not a story about overcoming past trauma and thriving. Instead, this is a story about the burdens we cannot escape and a core loneliness most people can never resolve.

I trawl through a lot of secondhand anime shops, especially when I visit Osaka. There’s an entire neighborhood about a fifteen-minute walk from the overwhelming bustle of Dotonbori known as Nipponbashi Denden Town. This is Osaka’s answer to Tokyo’s Akihabara, the hobby shop heart of a very cool metropolis. For my money, Denden Town has Akihabara beat tenfold when it comes to treasure hunting.

Recently, in Mandarake Grand Chaos, a towering shop whose six floors boast everything ranging from mecha kits to military cosplay, from figurines to artbooks, from Blythe dolls to city pop vinyl, from vintage film posters to idol cut-outs, from trading cards to Godzilla toys made in 1954, I came across something I rarely see: a piece of Bebop merch. It was a Jet Black figure by Pop Up Parade, a well-crafted collectible, for only 1400 yen (about 9 bucks). At any stateside convention, that thing would have already sold to some overjoyed fan. But in Osaka, it was relegated to the bottom of a nondescript shelf. Across the aisle was a large array of Macross figures. Watanabe worked on Macross Plus before he took on Bebop. In the States, despite a dedicated cult fandom that includes my good friend Bridget, Macross is not widely popular these days.

I set Jet back on the shelf and moved on to another floor to look at Pokémon cards, as those remain my true ’90 vice. I have heard there’s recently been a Magic: The Gathering-slash-Bebop collab, but I haven’t seen a lick of that. These days, MtG isn’t nearly as popular in Japan as Yu-Gi-Oh!, Duel Masters, and ONE PIECE trading card gamesare.

Even so, that lonely figure gave me something to think about.

Maybe, I’ll go back for Jet Black. Not for me, but for America.

Welp, I said I’d be doing a whole thing on anime space Westerns, but Bebop took over. I’ll save Trigun for another time because one can only handle so much nostalgia, so look forward to a piece on Frieren followed by a little love for Cherry Magic! Before we dive into spooky October with articles on Natsume’s Book of Friends.

In this article:

- Cowboy Bebop (Sunrise, 1998) Available via Netflix and Hulu.

Up Next:

- Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End (Madhouse 2023-2024) Available via Crunchyroll and Netflix.

- Cherry Magic! Thirty Years of Virginity Can Make You a Wizard?!(Satelight 2024)

- Natsume’s Book of Friends (Brain’s Base 2008-2012; Shuka 2016- ongoing)